|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Contents:

|

|

A bit of history

The first ideas for a pulsed tube curve tracer were conceived as far back as Christmas 2010. The first uTracer version used a high-side current sense circuit that did not really work satisfactorily. After a golden tip from somebody following my weblog, I changed the current sense circuit to its present concept, and the uTracer3 was born. Stimulated by my sons “to go commercial,” I designed a PCB for the uTracer3 in 2012 and later that year the first uTracer kits were on their way to the first customers.

How does such an undertaking work in practice? Of course the first experimental versions of the uTracer were constructed with components I had lying around. With the circuit working very satisfactorily, it was not more than logical to copy the circuit one-to-one for the commercial version of the uTracer3. At the time I estimated that perhaps, with a bit of luck, we would sell a few dozens of kits. I absolute could not have imagined that 12 years later there would be over 2600 uTracers in service in 63 countries!

Over the years, I discovered and experienced things that also real, large compagnies have to deal with. One of these things is that once you have a product running, it is not so easy to make changes to it. Over the years there have been two major changes to the design of the original uTracer. The first major change was the introduction of the uTracer3+ which raised the maximum voltage to 400 V, and the second change was a redesign of the PCB. Every change requires adaptation of the manual, changes in the components to be ordered, the production of a test series to make sure the kit is flawless, etc. Additionally, there is the issue of customer support. The uTracer is a rather complicated kit, and unavoidably mistakes happen during its construction. I always try to help everybody as good as I can via email, and if that doesn’t work out I am happy to have a look at the circuit myself, so you really want to limit the number of circuit versions to deal with to the minimum. In short, the choices you make in the beginning in terms of component selection and circuit topology may very well haunt you for years!

One of the things every electronic appliance company that sells products that run over many years must deal with, is that at a certain moment components become obsolete. It happens to big companies, like Philips where I work(ed), and tiny companies like Dos4ever. At a certain moment for example, it was announced that the original processor, the PIC16F874 would be taken out of production. The PIC16F884 was suggested as an almost pin compatible alternative. Nevertheless, it took me days of headache and many software changes to get it working. Also the original MJE350 and KSP99 high-voltage pnp transistors in the meantime have been phased out and had to be replaced with suitable alternatives.

The latest addition to the list of “soon to be obsolete” components is the DIL version of the OPA227! Already since COVID times, the availability of the OPA227 has given me a headache, while also since that time its price has skyrocketed! Apparently the SMD/SMT version of the OPA227 will remain in production somewhat longer, so to mitigate the upcoming problem, my first idea was to redesign the PCB to make it suitable for the SMD variant. However, thinking things over I started doubting if this would be the right way to go?

I have always been a strong fan of “old fashioned” through-hole components. Primarily, because most uTracer customers are tube/valve enthusiasts who, very often, do not have much affinity with tiny, fragile, difficult to handle and solder SMD components. Secondly, I always had the idea that servicing a circuit with through-hole components was easier than servicing a PCB with SMD components. I learned that although this certainly holds for IC’s in sockets, where the possibility of rapidly exchanging a part helps to quickly debug the circuit, I discovered that the situation may be completely the opposite for other components. Ever since I started using a hot air soldering station, I realized that especially replacing transistors is much easier if you have an SMD component instead of its through-hole counterpart! On top of that, the harsh reality is that many modern and powerful components are simply not available in through-hole packages anymore!

So, all this made me think and decided me not to go for a straightforward simple modification of the uTracer3 PCB, but instead to take a critical look at the whole circuit and come up with a more modern and future proof overhault: the uTracerNXT!

What’s in a name?

Being a man of exact science (and a bit autistic as well), my first idea was to name the redesign of the uTracer the - you may have guessed it - uTracer3.2. However, after hearing me talk about the uTracer3.2 for weeks, the CEO of our tiny family enterprise (my wife) expressed her discontent with the name. First of all, she thought it looked “ugly,” but she also thought that it was rather nondescriptive, not doing justice to the fact that the new design will also include a substantial number of innovations and improvements. “It’s a bit how kings or popes are numbered” was here objection. Since we already have a uTracer 4, 5, 6, 7 (that not all made it into a kit by the way) I started thinking of an alternative. For a moment I was tempted to call it the “FU2Tracer,” but I am glad I was sensible and didn’t go that route. Playing with words and letters I came up with NXTracer (Next Tracer) to emphasize that the new tracer is not just an upgrade of the old uTracer3+, but really a completely new design. However, then several readers pointed out to me that it would not be a good idea to discard the, in the mean time, well-known brand name uTracer (micro-Tracer), so in the end we settled for uTracerNXT, to be pronounced “Micro-Tracer Next” I tested the new name on my wife and sons, and they all liked it. So, there we have it, the uTracerNXT!

uTracerNXT wish list

Producing more than 2000 uTracer3+ kits, servicing them and getting feedback from users and adding to that new ideas and insights gained from the uTracer6 and the stillborn versions 4 and 5, resulted in a wish-list for the uTracerNXT.

New features / Modifications:

| to top of page | back to uTracer homepage |

Figure 2.1 shows a first plan for the analog circuit part of the uTracerNXT. It is by no means a definitive version, but rather a first draft to start working from. In the circuit many of the learnings gained from the uTracer6 but also the work on the uTracer7 have been implemented.

Going from the top to the bottom, the first two “rows” of the schematic as usual depict the anode and screen high-voltage supplies and switches. One of the changes in the uTracerNXT with respect to its two predecessors is that the cathode of the tube is referenced to ground rather than to the + of the supply voltage. The reason for this was that normally the output voltage of a boost converter cannot be lower than its supply voltage. However, by simply adding Zener diode D61 with a breakdown voltage higher than the supply voltage in series with high-voltage blocking diode D60, allows the output voltage of the boost converters to go down to 0 V. The potential penalty for this trick is a little but lower efficiency, but we will have to see how serious that is.

Moving to the left, the “normal” diode in parallel to the current sense resistor R62 has been replaced by a Zener diode. The idea is that during the charging of C60 the Zener diode is conducting, just like a normal diode, and that during discharging – that is the measurement pulse – the Zener diode is in reverse bias and in that way protects OpAmp IC61 for high input voltages, e.g. during a short circuit at the output of the anode supply. The circuit around the current sense OpAmp and the PGA IC62 is pretty standard, with the exception of resistor R67, which sinks a small current from the output of the OpAmp to the negative power supply. The idea is that this will help the output of the OpAmp to really go down to its negative supply line, 0 V. The reason is that although most OpAmps these days are advertised as having rail-to-rail outputs, what really is meant is almost rail-to-rail. More in this the next section.

The high-voltage switch is identical to the circuit used in the uTracer6. The circuit is extensively described in the uTracer6 weblog. At the writing of this page, there are more than 500 uTracer6 in service in 49 countries. So far, not a single failing high-voltage switch has come to my attention. For me reason enough to copy the circuit one-to-one for the uTracerNXT. The only change is that the 1000 V STD2NK100Z NMOS transistors have been replaced by the readily available 700 V IPD70R360P7. As usual the screen circuit is identical to the anode circuit.

Moving down to the bottom part of the circuit, we find the heater, negative grid bias power supply and the +5 V power supply. Missing here, compared to the uTracer3 and 6, are the +15 V and -15 V power supplies, which saves a lot of overhead. The -105 V negative grid bias power supply uses a -400V FQD2P40 PMOS transistor instead of the BD138 pnp transistor in the uTracer3, which I expect to result in a more reliable operation.

Similarly, the grid bias supply also follows the design used in the uTracer6, be it with different components. A LM4040 “Zener” diode, provides a stable 2.5 V reference voltage to the DAC. As DAC the readily available 12 bit MCP4921 from MicroChip is used. The MCP4921 is programmed via a serial SPI bus, and by using the onboard 2x amplifier, the output voltage can be programmed to be between 0 and 5 V. An OPA454 High-Voltage OpAmp from TI is configured as a 20x inverting amplifier which boosts the output voltage from the DAC to a voltage between 0 and -100 V. Just like in the uTracer6 I intend to use the grid bias in pulsed mode by means of T40 to limit the power dissipation in the OpAmp, especially for conditions where the output is for some reason short circuited. The reason I plan to use an OPA454 is because it seems to have a better availability than the LTC6090 from Analog Devices used in the uTracer6. D41 and R45 protect the OpAmp against flashovers in the tube and short circuit conditions.

Figure 2.1 First tentative draft of the (analog part) of the uTracerNXT circuit. For this circuit diagram I used the the schematic of the uTracer6 as starting point, so component numbering may be inconsistent.

| to top of page | back to uTracer homepage |

The idea to use a Zener diode to modify the standard boost converter so that it can produce output voltages down to 0 V originates from the work on the uTracer5, a version that never made it into a fully working concept. The working is very simple, a 24 V Zener diode simply blocks the supply voltage so that when the transistor is not pulsed the output remains at zero volt. However, since the Zener diode is in the high-voltage pulse path, the question is what the penalty is in terms of efficiency.

This question was investigated using the test circuit shown in Figure 3.1., which is the boost converter stripped down to the core circuit. For the MOSFET a IPD70R360 from Infineon was used. This “CoolMOS” device is rated at 700 V @ 300 mohm and 12 A. It has a Vt of 2.5 V so that it can be directly driven by a 5 V TTL level signal without the need for a special gate driver. In the circuit, it is driven by a 5 V pulse generator with a frequency of 10 kHz and a variable duty cycle. When S1 is closed, C1 is charged (monitored by a voltmeter, not drawn). Note, how in this circuit the UF4007 diode that in the uTracers 3 and 7 shunts the current sense resistor R2 is replaced by a Zener diode. This Zener diode has two functions. During the charging of C1 the diode is in normal forward mode, limiting the voltage drop over R2. During the actual measurement pulse, the current through C1 and R2 is reversed, resulting in a negative voltage drop across R2. R2 is selected in such a way, that in normal use this voltage drop never exceeds -5 V. However, when an excessive current is drawn, e.g. as a result of a short circuit at the output, the voltage drop across R2 can become so high that it potentially could damage the inverting OpAmp connected to R2. In these situations the Zener diode limits the voltage transient to 7.5 V, thereby protecting the OpAmp.

Figure 3.1 Test circuit for the zero-volt output boost converter and measurement results

The table in Fig 3.1 shows the measurement results. Measurements were carried out at 10, 15 and 20 V supply voltage and a pulse duty cycle of 20% as well as 30% corresponding to charge pulse widths of 20 and 30 us respectively. What was measured is the time it takes for the boost converter to charge C1 to 400 V with and without the 24 V Zener diode. Normally for the uTracer circuit a supply voltage of 20 V and a boost converter pulse width of 30 us is used. Note that under these conditions the difference in charging time is negligible!

As mentioned in the introduction, the OPA227 that was used in the uTracers 3 and 6 is increasingly getting difficult to obtain, especially in the DIL/DIP package. The OPA227 was originally selected for its low offset voltage (10 uV typically and 200 uV max) combined with a reasonable slew rate of 2.3 V/us. A low-cost modern alternative like the MCP6V86 offers a similar or even better performance with an offset voltage of +/- 25 uV max, combined with a slew rate of 4 V/us. However, this device is designed for a single supply voltage of 5V.

The problem is that, although these devices are advertised as having “rail-to-rail” inputs and output, the truth is that the output cannot really reach the negative or positive supply rails. The reason is that the quiescent current running through the output stage of the OpAmp always causes some voltage drop as a result of the finite on-resistance of the output MOSFETs. For the MCP6V86 for example, the datasheet specifies an ouput voltage swing of Vss + 5 mV and Vdd – 5 mV. That does not seem much, but 5 mV corresponds to an error in the measured anode (or screen) current of 5 mV / 18 = 280 uA, assuming that a 18 ohm current sense resistor is used.

Figure 3.2 Simple adaptor to test the MCP6V86 in an OPA227 socket.

Browsing the internet to have a look at how others solve this problem, I ran into various interesting solutions. A very surprising find was the LM7705 which is a “Low-Noise Negative Bias Generator,” an integrated switched capacitor inverter that produces a -0.23 V negative supply for an OpAmp to allow its output to really swing to 0V.

A simpler solution was presented in an application note from TI entitled “”Single Supply Op Amp with True Drive to GND.” The solution uses a pull-down resistor at the output of the OpAmp which is connected to a negative supply to provide a path for the output stage current to the negative supply. When the output of the OpAmp is driven to Vss (ground in this case), the output NMOS transistor in the OpAmp will now turn fully off allowing the output to swing to 0V. Of course, this requires a negative power supply, but as it happens, we very conveniently already have one in place for the negative grid supply!

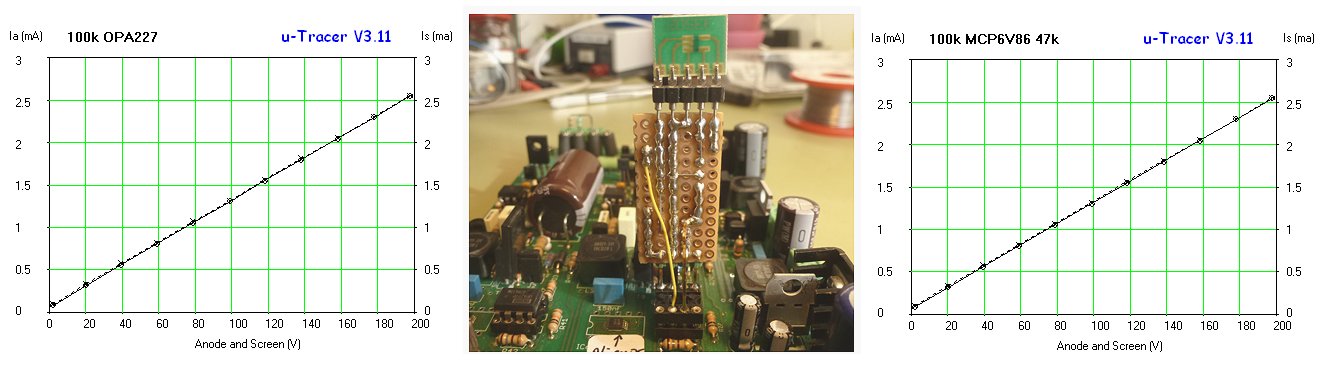

To quickly test the idea, a simple adaptor was built to fit the tiny MCP6V86 into the DIL socket of an OPA227. The adaptor comprizes an LM78L05 to reduce the +15 V supply voltage to +5 V, and a pull down resistor which is connected to the -15V supply. The application note states that as a rule of thumb the output stage of an OpAmp consumes about half of the total quiescent current of an OpAmp, so for the MCP6V86 approximately 500 uA / 2 = 250 uA. For a negative supply voltage of -15 V this requires a 15 / 250 uA = 60 kohm pull doen resistor. I used a slightly lower resistance of 47 kohm. For the real circuit with a -105 V grid supply the value of these resistors (R67 and R87 Fig 3.2) will need to be increased to 105 / 250 uA = 420 kohm.

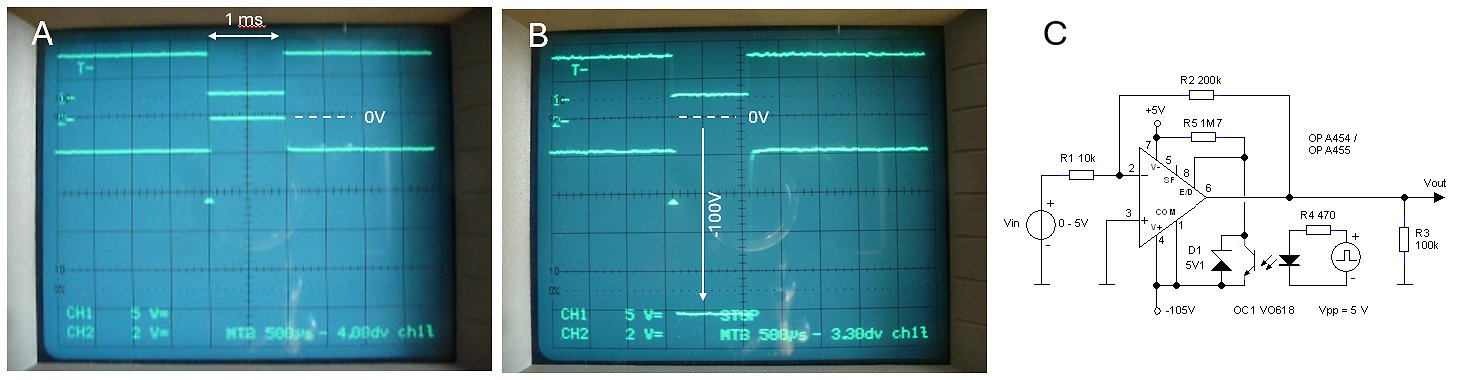

Figure 3.3 First tests with the MCP6V86 adapter in an uTracer3+.

In a first test in a uTracer3 the plugin circuit worked like a charm! Figure 3.3 shows the MCP6V86 adapter board replacing the screen OPA227 in a uTracer3+. The left graph shows a trace of two 100k resistors connected to the anode and screen outputs using the original circuit with two OPA227s, while the right graph shows the same measurement using an OPA227 for the anode section, and the MCP6V86 adaptor for the screen. Find the differences!

Figure 3.4 Test circuit and measurement results of the MCP6V86 for very low input voltages, with and without output pull-down resistor.

To study the offset and output-to-negative supply voltage standoff behaviour of the MCP6V86, the circuit shown in Fig. 3.4 was used. The OpAmp is configured as an inverting amplifier with a gain of -1000x. The 10 Mohm resistor basically acts as a current source to the 10 ohm resistor R2. In this way, a voltage V- = -10V will result in a input voltage of Vin = -10 uV across R2, and thus ideally in +10 mV at the output of the OpAmp. The graph in Fig. 3.4 shows the output voltage of the OpAmp as a function of input voltage Vin. The combined effect of the OpAmp’s offset voltage and output-to-negative supply voltage standoff for this OpAmp without an output pull-down resistor at Vin = 0 V is only 4.5 mV! With the pull-down resistor of 47 kohm the output voltage at Vin = 0 V drops to 1 mV. These measurements suggest that the input referred offset voltage of this OpAmp is 1 uV, while the output standoff voltage is 3.5 mV. The datasheet of the MCP6V86 does not give a typical offset voltage only maximum values of +/- 25 uV, so for this particular device 1 uV is indeed excellent, but potentially it could be higher. The output standoff voltage of 3.5 mV is in good agreement with the datasheet.

The high-voltage switches connect the charged 100 uF capacitors to the anode and screen terminals of the tube during the 1 ms measurement pulse in which the currents are measured. A particular design requirement of the switches is that the switches are completely floating with respect to the rest of the circuit to ensure that all the current is passed through to the current sense resistor in series with the 100 uF capacitor.

The high-voltage switches connect the charged 100 uF capacitors to the anode and screen terminals of the tube during the 1 ms measurement pulse in which the currents are measured. A particular design requirement of the switches is that the switches are completely floating with respect to the rest of the circuit to ensure that all the current is passed through to the current sense resistor in series with the 100 uF capacitor.

The anode and screen high-voltages switches in the uTracer3+ were based on a PNP switch design. Although it worked fine in more than 2500 uTracers, from time to time the switch tended to fail as a result of massive short circuits at the output, or violent oscillations in the tube circuit. Another point of concern is that high-voltage, high power pnp transistors are increasingly becoming obsolete, if not non-existent at all. It was the reason why the high-voltage switch circuit was completely redesigned for the uTracer6 which operates at voltages up to 1000 V. The uTracer6 high-voltage switch circuit is based on a readily available high-voltage NMOS transistor. The development of the switch circuit is extensively described in the uTracer6 weblog pages.

In the 450 or so uTracer6’s “in the field” the NMOS high-voltage has shown to be very reliable, with no failures reported to date! Reason enough for me to copy and adapt the circuit for the uTracerNXT. The principal circuit is reproduced on the left. Basically the only modification to the circuit is the replacement of the 1050 V STD2N105K5 NMOS transistor by a readily available 700 V IPD70R360 transistor made by Infineon.

| to top of page | back to uTracer homepage |

Although the grid bias section of the uTracer3 served its purpose perfectly, it is a bit of a strange circuit. In the first place because it uses as DAC one of the PWM outputs of the PIC combined with a low pass filter, and in the second place because it had to be referenced to the cathode potential, in this case basically the positive supply voltage. Furthermore, the grid voltage range was limited to 0 to -50 V, and over the years I got a lot of requests - especially from people who want to trace/test tubes like the 300B - to extend that range to (at least) -100 V.

Figure 4.1 Basic idea for the uTracerNXT grid supply.

Now that I am going though a major revision of the circuit anyway, it seems like a good moment to revise the whole grid supply concept. The fact that the grid voltage is now referenced to ground instead of the supply voltage makes things a lot easier. Figure 4.1 left shows the simple plan. Simila to the uTracer6, the circuit is again based on a high-voltage OpAmp. The LTC6090 from Anaglo Devices that is used in the uTracer6 has given me quite a bit of headache. In the first place because it is sometimes difficult to source, and secondly because its price has really soared since the COVID semiconductor shortage. This time I want to bet on an OpAmp from Texas Instruments, the OPA454 with a maximum supply voltage of 100 V or perhaps even the OPA455

with a maximum supply voltage of 150 V.

The idea is to supply the OpAmp from the +5 V supply voltage and a -105 V negative supply voltage. The few volts overhead will allow for the output to comfortably swing between 0 and -100 V. The grid voltage is controlled by an SPI controlled 12 bit DAC for which I have the commonly available MCP4921 in mind in combination with an LM4040C25 2.5 V reference. Most ideal would be to have a single range of 0 to -100 V with high precision and low offset. However, although the datasheet of the OPA455 specifies a typical offset of 0.2 mV, the maximum offset is specified at 3.4 mV. With a gain of 100 / 5 = 20, an offset of 3.4 mV at the input will result in an output offset of 20 x 3.4 = 65 mV which is rather high.

It seems therefore a good idea to at least create the possibility to split the grid voltage range up in a 0 to -25 V range for general tubes, and a 0 to -100 V range for tubes like the 300B and transmitter tubes. So, using a jumper or a switch, the OpAmp can be configured as a -20X or -5X amplifier. The table in Fig. 4.1 gives for both ranges the grid voltage resolution, and both the maximum as well as the typical offset voltage to be expected. With a bit of luck, the offset voltage is low enough so that the 0 to -100 V range will suffice for most tests.

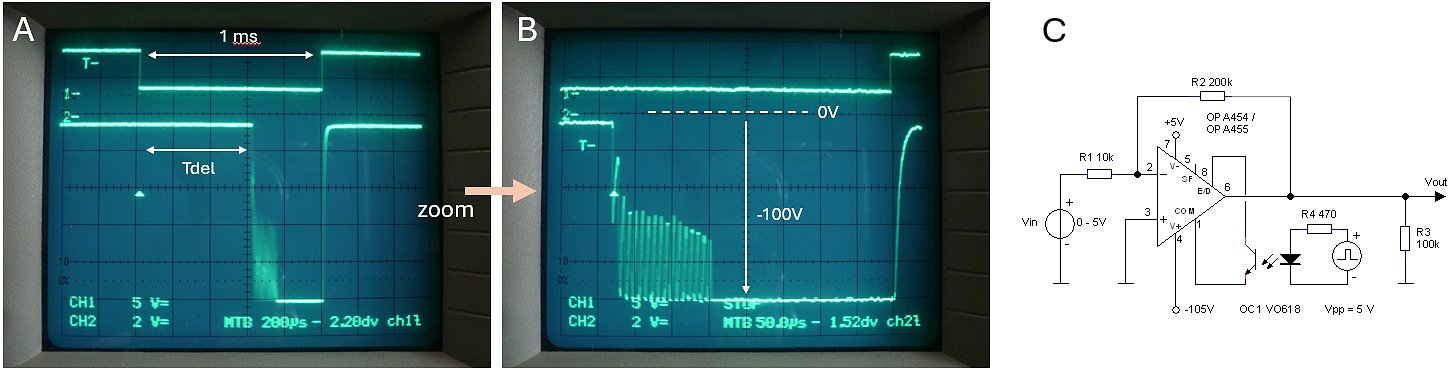

Figure 4.2 First attempt to enable / disable the OPA455 using an optocoupler. The upper trace is the signal driving the LED in the opto coupler.

When the level is low, the LED is off, and the phototransistor is not conducting.

Like in the uTracer6, the grid supply will work in pulse mode, whereby the OpAmp is only enabled during the actual measurement pulse. The main reason is to limit the dissipation in the OPA455 and thus to prevent the need to use the thermal pad of the device, which is a nightmare for simple hobbyists. This is relevant in normal operation, but especially also when the grid output is short circuited. During a short circuit or a flashover from screen or anode, the output of the circuit is protected by Rp and D1. In case of a flashover the OpAmp is protected against positive voltages by D1 while Rp limits the current. In case of a short circuit to ground Rp limits the output current of the OpAmp to a safe value of 30-40 mA. Although the OpAmp can sink that current continuously, it would cause considerable dissipation in the device. Operating the supply in pulse mode virtually eliminates this. Additionally, the resistor acts a grid stopper, reducing the chance on oscillations.

Operating the Enable / Disable (E/D) input of the OPA455 turned out to be more difficult than expected. The E/D input is referenced with respect to the E/D Com pin. A logic high on the E/D pin enables the OpAmp, a logic low disables it. A “high” on the E/D pin may not exceed 7 V with respect to the E/D Com pin. There is considerable freedom to define the E/D Com level, but one way or the other with the highly asymmetric supply voltages I am using here it, at least for me, it turned out to be impossible to operate the E/D pin in the conventional way with E/D Com referenced to ground. In fact, I destroyed two OPA455 OpAmps while experimenting with the circuit.

Figure 4.3 Improved Enable / Disable optocoupler drive for the OPA455.

A solution was suggested in the datasheet of the OpAmp which states “when E/D Com and E/D are left open, the OpAmp is enabled, when E/D is connected to E/D Com, the OpAmp is disabled.” Using a simple optocoupler between the two pins made it possible to connect or disconnect the two pins while leaving them completely floating with respect to the system ground (Fig. 4.2). The idea worked, but not without issues. As can be seen (Fig. 4.2 left), there is a considerable delay between the LED of the optocoupler switching off and the OpAmp switching on. Additionally, there is some oscillatory behavior as the OpAmp switches on. Both phenomena can be attributed to the low currents and thus high impedances by which both pins are internally biased.

The datasheet of the OPA455 states that the E/D Com pin can be connected to the negative power supply rail without problems and also suggest using a pull-up resistor to prevent oscillations (Figure 7-1 datasheet). Implemented these measures (Fig. 4.3) not only solved the switch-on delay, but also eliminated the oscillations.

The datasheet of the OPA455 mentiones another peculiarity of the OPA455, and that is that in disabled mode, the output impedance of device is not infinite, but around 160 kohm. This explains why in figures 4.2 and 4.3 the off-level is not exactly 0 V. For our application, this is obviously not a problem.

| to top of page | back to uTracer homepage |

Figure 5.1 Updated schematic of the uTracerNXT

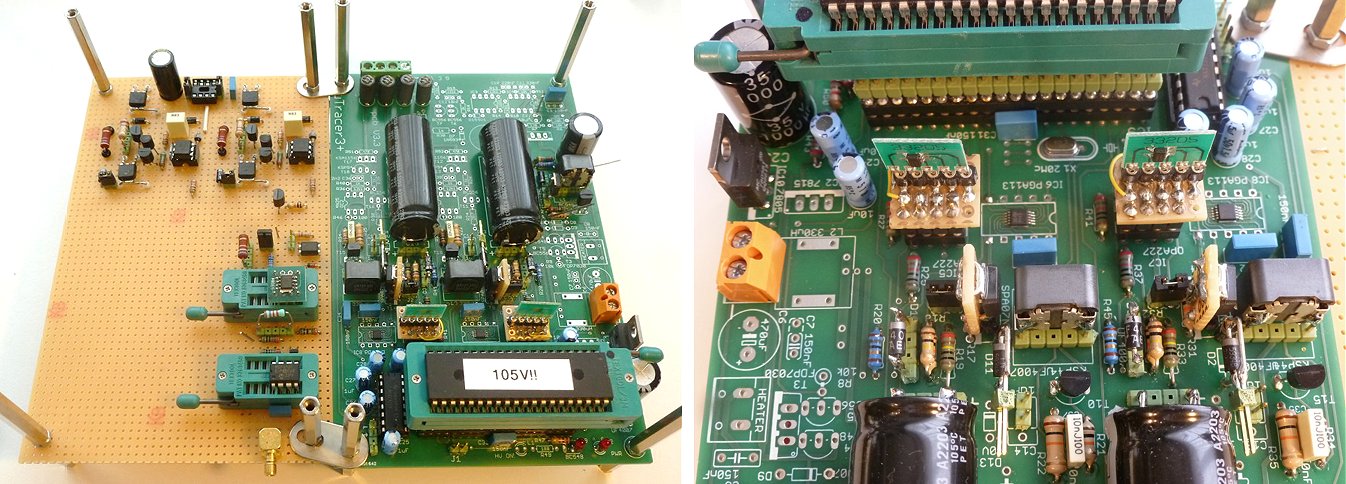

For the construction of the prototype a half populated uTracer3 PCB was married to a piece of perf-board (Fig. 5.10). Two adapter PCB’s were used to fit the MCP6V86U OpAmps into the OPA227 sockets. New is the vertical mounting of the inductors (mis)using modified pin headers. It appeared that the normal mounting of the inductors sometimes results in some bad connections because people find it difficult to solder them. In this way that problem is solved, and I think I will also implement this method in the final kit. For the prototype I used two of the 100 uF / 500 V capacitors that are also used in the uTracer6. This allows me to go to 500V anode and screen bias. Two ZIF sockets were used for both the MCP4921 DAC as well as the OPA455 high-voltage OpAmp. This makes it very easy to test different components e.g. to look at the spread in offset voltages etc.

In the uTracer3 both the “power-on LED” as well as the “HV-LED” were fed from the +5V supply using a 180 ohm resistor resulting in a current of 20 mA / LED, almost 6 times the current consumption of the PIC! By powering these LEDs directly from the +19.5 V supply, the current consumption on the +5V is so much reduced that the heatsink can be eliminated. Quite a large number of jumpers were used to be able to isolate certain circuits parts in this evaluation phase. Although the circuit looks quite large, I am sure that when all the adapter PCB’s, jumpers etc. are omitted the complete circuit will easily fit on a PCB with the same size as used for the uTracer3.

To reduce the charging time for the higher anode and screen voltages of 500 V, the charge pulse width for the high-voltage boost converters was increased. According to the datasheet of the 330 uH inductors, they saturate at a current of 2 A. At that current the inductance, by the way, is already reduced to 70%. The current I through an inductor L for an applied constant voltage V for time t is given by: I = (V*t)/L. So the time needed to reach a current I is given by t = (I*L)/V. For V = 20 V, I = 2 A, L = 330 uH, we find t = 33 us. To be a bit on the safe side, the boost converter pulse width was increased to from the 24 us that was used in the uTracer3 to 29 us in the new design. This reduced the time to charge the 100 uF capacitors to 500 V from 9 to 4.5 seconds.

Figure 5.2 Low current performance without (left) and with (right) the OpAmp output pull-down resistors.

Figure 5.2 shows the necessity of the pull-down resistors at the output of the current sense OpAmps. Without the resistors basically no current measurements below 500 uA are possible. The pull-down resistors of 330k connected to the -105 V negative supply rail provide a near ideal current sink of 105V / 330 k = 320 uA, resulting in a near linear operation down to 10 uA.

Figure 5.3 Top: anode and screen current measurements over three decades using a 18 ohm current sense resistor.

Bottom: anomalies observed with open output.

Figure 5.3 illustrates the anode and screen current measurement performance over three decades of current from 200 mA down to the tens of microamps range using an 18 ohm sense resistor. From experience with the uTracer3 this is a practical range for most common tubes. It is always possible to reduce the value of the current sense resistor should higher currents be necessary, of course at the expense of a somewhat noisier performance at the low current end range. Read more here and here.

By accident I observed an anomaly when the anode terminal of the circuit was connected to a load (resistor), while the other was left open, or visa versa. The left-bottom graph of Fig. 5.3 shows how suddenly at a certain voltage the screen current jumps to some high value and then return to zero again. It was found that even with the tiny load of a 1 M resistor connected to the screen terminal the behavior was normal again. The origin of the phenomenon was traced back to the discharging of the high-voltage switching circuit. Observe that the whole high-voltage switch circuit is electrically floating, and that its potential moves up and down with the output voltage. When suddenly the output transistor opens, the whole circuit has to discharge through the load at the output. The three scope traces in Fig. 5.3 show on the upper channel the measurement pulse issued by the PIC and on the lower trace the screen output voltage, and that for three different loads. With a 10 k resistor connected to the screen terminal, the width of the output pulse is identical to the measurement pulse as issued by the PIC. So, the 10 k resistor discharges the high-voltage switch circuit very fast. With a 1 M resistor connected to the screen terminal we see that it takes some time for the output voltage to reach zero. With an estimated time constant of approximately 3 ms this leads to the conclusion that the effective capacitance of the high-voltage switch circuit to ground is in the order of 3 nF. With no load connected apart from the 10 M resistance of the 10:1 scope probe the discharge time becomes even larger. It is obvious to assume that with no load at all, the output is still charged before the next measurement pulse is issued.

The issue can easily be remedied by permanently connecting a 1 M load resistor between the output and ground. Obviously, this will increase the output current, but since both the output voltage as well as the resistance value are known, this additional current can easily be compensated for by the software in the GUI.

Figure 5.4 Offsets in the grid bias circuit.

The idea behind the control grid supply circuit is very simple (see figure 4.0). A 12 bit DAC provides a programmable voltage between 0 and 5 V. Then a -20x amplifier converts this into a 0 to -100 V voltage. Unfortunately, the situation is not as simple as that due to non-idealities in especially the DAC and the high-voltage OpAmp. First of all, although the DAC is claimed to be “rail-to-rail,” as explained in the previous section, this in practice means “almost rail-to-rail.” For a programmed 0 V output voltage, in practice the output voltage will saturate to a finite value, which according to the datasheet (Fig. 5.5) can be as high as 10 mV. Although this is not really an offset voltage, nevertheless in Fig. 5.4 this is represented by an offset voltage Vo1. Additionally, the high-voltage OpAmp can have an offset voltage which, according to the datasheet (Fig. 5.5) can vary between +/- 3.4 mV, although the statistical distribution graph from the same datasheet shows that in practice the offset voltage will be much smaller. The equation in Fig. 5.4 shows how these two offset voltages result in grid voltage offsets varying between -270 mV and +71 mV, which is unacceptable for accurate measurements on tubes e.g. like the ECC83.

Figure 5.5 Measured offsets in the DACs, OpAmps and the complete circuit; and excerpts from the data sheets of the MCP4921 and OPA455.

The get a feeling of the extent of the problem, I did some measurements using the prototype setup with two OPA455 OpAmps on adapter PCBs and eight MCP4921 DACs: one SMD version and 7 DIL packaged devices (Fig. 5.5 left). For these measurements, the gain of the OpAmp was set to -20x. For the first set of measurements the DAC was removed from the ZIF socket and the input of the OpAmp amplifier circuit was connected to ground, and the output voltages for the two OpAmps were measured indicating offset voltages of: OpAmp1 -19.8 mV / -20 = +0.99 mV, OpAmp2 -7.4 mV / -20 = +0.37 mV. Next the DACs were inserted and both the DAC output voltage, as well as the amplifier output voltages were measured. Most DACs exhibited a low “offset” voltage of 1.2 mV, however, there was one “bad boy” with an offset of 7.3 mV which, by the way, is still within specifications. It is gratifying to see that the resultant OpAmp output voltages closely follow the theory.

Figure 5.6 Principle of offset correction in the uTracerNXT.

If the resultant offset voltage at the output of the OpAmp is positive, then it can be simply compensated for in software by defining a new n’(Vgrid) = n(Vgrid) + ncorr, or in other words “shifting the y-axis.” However, as we have seen, it is more likely that the resultant offset at the output of the OpAmp is negative. Figure 5.6B shows this situation. In this case, it is not directly possible to compensate for the offset in software. A solution is to “shift” the entire curve up, so that the offset becomes zero or even positive. The equation in Fig. 5.4 suggests how this can be done. Introducing a deliberate positive Vo2 will shift the curve upwards. The schematic in Fig. 5.1 shows how this is implemented in the uTracerNXT. A relatively large resistor R43 connected to the 2.5 V reference voltage bleeds a small current through the 10 ohm resistor R44 causing a deliberate positive offset shift. As an example for R43 = 10 k, the shift at the input is 2.5 mV; with a gain of 20x this results in an offset voltage at the output of the OpAmp of 50 mV.

Figure 5.7 Implementation of the control of the grid supply in the GUI.

Figure 5.8 Measured offsets after calibration over the full control grid bias range.

So, how well does all this work out in practice? Figure 5.8 shows the result of the grid bias circuit evaluation using a DAC with a low-offset (left) and the DAC with a high-offset, the bad-boy (right). Looking at the low-offset DAC, we see that the initial offset was -11.5 mV. Using a 10k resistor for R43 this was lifted to +12.1 mV. For a gain of 20 (the zero to -100 V range) the grid voltage in the GUI was set to the mid-range value Vgrid = -50 V. Next the slope correction factor α was adjusted so that the measured Vgrid was -50 V. Next, the grid voltage was set to a very low value - I used -200 mV - and ncorr was set to such a value that the measured grid voltage was as close to -200 mV as possible. After the calibration the grid voltages for set point values between zero and -100 V were measured and the error recorded. The same procedure was repeated for the zero to -25 V grid bias range. Finally, the high-offset DAC was evaluated in the same way.

We observe that over two orders of magnitude from Vgrid = -1 V to -100 V the deviation in the grid voltage is less than 1%. Below -1 V the error increases with a maximum of around 3%, from the graphs in Fig. 5.8 this looks more serious than it is. Note that a few percent deviation is hardly something to worry over in “tube world.” Also note that after calibration the high-offset DAC performed even slightly better that the other one. I think that with more careful calibration, e.g. by using a different test voltage for the “ncorr calibration step”, the overall accuracy can still be improved. All in all, I am quite satisfied with the performance of this simple and cost-effective circuit!

Firmware and GUI updates

Both in the firmware as well as in the GUI a number of changes and updates have been made. Whereas the changes in the GUI are limited to the way the different voltages are calculated, in particular taking into account that anode, screen and grid voltages are now referenced to ground. The changes in the firmware are more substantial, and in part very similar to changes implemented in the uTracer6:

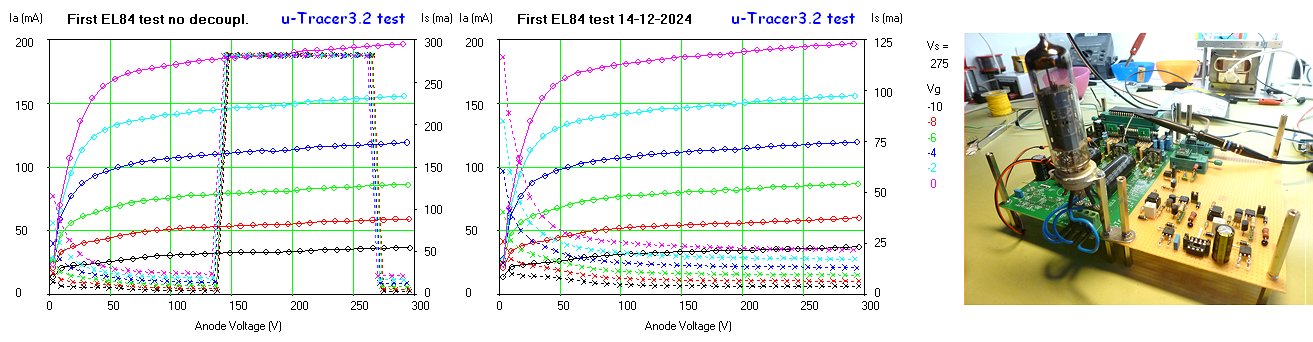

Figure 5.9 First tube measurements with the uTracerNXT

With the control grid section in place and calibrated, it was time for the first tube measurements. Test vehicle was of course my trusted EL84 (Fig. 5.9). To my surprise and disappointment, the same strange phenomenon observed in Fig. 5.3 returned! Suddenly, the screen current jumps up to the maximum value, to return to normal values for higher voltages (Fig. 5.9 left). After a lot of searching, I concluded that there was nothing wrong in the signal path to the point of the PGA input, so that the fault had to be related to the PGA113. Could it be that noise on the +5V supply to the PGA caused it to behave in a strange way? Indeed, a small 47 uF capacitor placed directly over the supply terminals of the PGA113 solved the problem completely (Fig. 5.9 middle). Obviously, the ad hoc wiring of the prototype is far from ideal and most probably the root cause of this hiccup. Anyway, something to keep in mind for the final PCB layout.

Figure 5.10 uTracerNXT prototype

| to top of page | back to uTracer homepage |

| to top of page | back to uTracer homepage |

The heater supply for the uTracer3 was originally designed as a simple and cheap add-on circuit that conveniently made use of one of the unused PWM outputs of the processor. Much has been said and written about its accuracy. Its main Achillis heel was that the PWM operated at a high frequency of 19.5 kHz. As a result, any (parasitic) inductance in the heater wiring markedly lowered the effective power delivered to the filament (read more here). For this reason, many users of the uTracer opted to add an external heater supply, often provided with a digital voltage and current readout. For the uTracer6 I decided to use the same circuit idea, be it operating at a much lower frequency, which greatly improved the accuracy. Although I could have gone for a much more elaborate heater circuit, this really doesn’t make much sense. As explained in the uTracer6 Weblog, there are so many cheap and excellent ready-made alternatives on the market, that I can never compete with those.

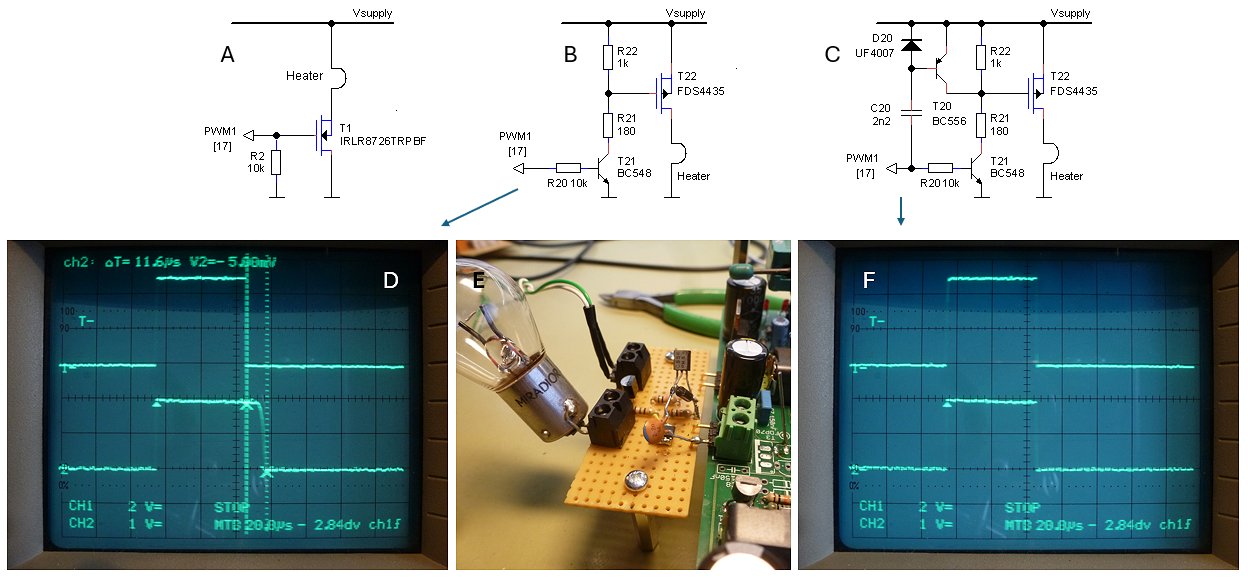

A change with respect to both the uTracer3 as well as the uTracer6 is that in the uTracerNXT the cathode is referenced to ground instead of to the positive power supply voltage. This implies that whereas previously the heater was simply connected to the positive supply voltage and driven by a single NMOS transistor, in the uTracerNXT - to accommodate directly heated tubes - the heater on one side must be connected to ground, so that it needs to be driven by a “high-side” PMOS device. This makes the circuit a little bit more intricate.

Directly heated tubes have the tendency to draw a lot of heater current at low voltages. Especially transmitter tubes can easily consume many amps of heater current at only a few volts. These high currents are obviously out of reach for the internal heater supply of any uTracer. So to test these tubes an external power supply is needed. For the uTracer3 this required the use of a DC power supply, because an AC supply would interfere with the accurate setting of the grid voltage, introducing noise in the measurements. For the uTracer6 extension board a simple add-on was developed to be able to use an AC heater source – a transformer – by synchronizing the measurement pulse with the AC voltage. For the uTracerNXT I decided to include the same option, so that it is now possible to accurately measure tubes like the 300B (5 V @ 1.2 A), 2A3 (2.5 V @ 2.5 A), 812A (6.3 V @ 4 A), etc. using an external transformer as heater supply.

Referencing the heater supply to ground

Figure 6.1 Heater circuit variations. The upper traces in the scope pictures are, top: the PWM input signal (2 V / div), bottom the heater voltage (10 V / div).

Referencing the heater to ground at first sight seemed rather straightforward, a suitable PMOS transistor connected to the supply voltage with a low-side npn transistor driving the gate (Fig. 6.1B). However, on testing it, the trusted 6.3V lamp I always use to test the heater supply burned much brighter that I was used to. What I had overlooked was that the high current PMOS has about 6 times the gate capacitance compared to the high-voltage PMOS transistors I usually use in the negative power supply boost converters. So, for the 1k resistor it takes about 11.6 us to switch off the transistor (Fig. 6.1D).

How serious is that? Remember that the PWM duty cycle is given by η = (Vh / Vsupl)^2, with Vh the set heater voltage and Vsupl the supply voltage. In the measurement shown in Fig. 6.1, the heater voltage was set to 5 V. So with Vsupl = 20 V and a PWM frequency of 1.2 kHz, the nominal PWM pulse width needs to be 51.2 us. Extending the PWM pulse to 62 us will result in an apparent heater voltage of 5.5 V. So where in the past when we were bitten by parasitic inductances the effective supply voltage of the heater was too-low, now it is too high!

Fortunately, there was a simple remedy for the problem (Fig. 6.1C). During the rising edge of the input PWM signal, C20 is discharged (or charged is you like), through diode D29. Then, at the trailing edge of the PWM signal, the inertia of the capacitor “pulls-down” the base of T20, causing it to conduct, thereby quickly discharging the gate of T22. The bottom trace of Fig. 6.1F shows the improvement. The circuit trick worked so well that I also used it for the negative power supply.

AC heater supply synchronization for DHTs

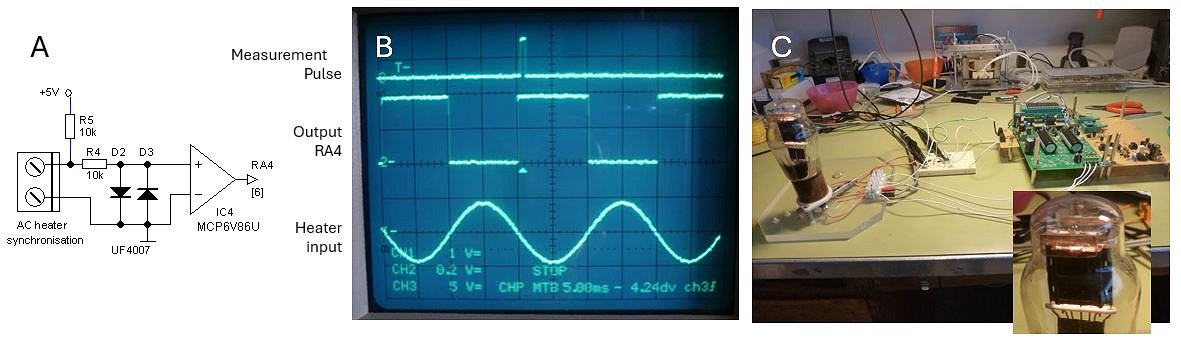

Figure 6.2 A: Zero-crossing detector, B: The AC heater synchronization circuit in action. Note how the measurement pulse (upper trace) practically coincides with the zero-crossing of the AC heater voltage, C: Test-setup around a 10Y DHT.

To allow for an AC heater supply for DHT tubes, the timing of the measurement pulse needs to be synchronized with the AC heater voltage, preferably in such a way that the moment of measurement coincides with the zero crossings of the heater voltage. For the zero-crossing detector several “one transistor type” circuits were considered, but in the end, I opted for the circuit depicted in Fig. 6.2. In the circuit the MCP6V86 OpAmp is misused as a comparator. The AC heater voltage is fed via current limiting resistor R4 to the input of the OpAmp, while diodes D2 and D3 limit the voltage to +/- 0.6 V. To prevent random toggling of the output in the absence of an input signal, resistor R5 pulls-up the input voltage so that the output of the OpAmp becomes permanently high.

A very small piece of code was added, which just before the grid bias is enabled and the measurement pulse is issued, checks input pin RA4 to wait for a 0->1 transition. When a transition is found, the routine exits and a measurement follows. In case no transition is found in 24 ms, there is apparently no AC signal present and a measurement follows anyway (see pseudo code below).

CNT := 140

AC_OLD := portA.4

do forever

delay 0.1534 ms

CNT := CNT – 1

if CNT = 0 then return ‘no 0->1 transition found

if portA.4 = 1 then

if AC_OLD = 0 then return ‘0->1 transition found

else

AC_OLD := 0

end if

end do

Figure 6.3 Set of curves taken from the 10Y DHT with heater, A: Fed from a 7 V DC source, B: Fed from a 7 V AC transformer without synchronization, C: The same with synchronization.

Figure 6.2C shows the test-setup used to test the heater synchronization circuit and firmware. It turned out that an old 10Y triode was one of the few, if not the only DHT tube I have apart from some very heavy-duty transmitter tubes. The traces in Fig. 6.2B show the synchronization circuit in action. The upper trace shows the measurement pulse which is used to trigger the scope (note that in this case a 0.5 ms measurement pulse was used). The lower trace is the AC voltage applied to the heater, while the middle trace depicts the output signal of the zero-crossing detector circuit. Note that there is a tiny 0.5 ms delay between the zero-crossing and the measurement pulse which is caused by a short software delay inserted to stabilize the tube between the moments the grid voltage and the anode/screen voltages are applied.

Figure 6.3 shows the effect of the heater synchronization. Figure 6.3A shows a set of output curves taken from the 10Y using a DC 7V heater supply. In Fig. 6.3B a 7 V transformer is used to power the heater without any synchronization. Because the moment of the measurement pulse is now completely random with respect to the AC voltage, the effective grid voltage varies drastically from point to point, resulting in very noisy curves. In Fig. 6.3C again a transformer is used, but now the synchronization circuit is connected to the heater. Note, that there is a (small) difference between the current values using the DC heater power supply and the transformer. This is caused by the fact that in the case of the synchronization circuit, the complete heater filament is at 0 V, while in the case of the DC heater supply the 7 V heater voltage is distributed over the filament, resulting in a slightly higher (more positive) effective grid voltage (see also Fig. 15-4 here).

For another example of a measurement of a directly heated tube with the heater powered by a transformer have a look at this trace of a very nice “45” tube.

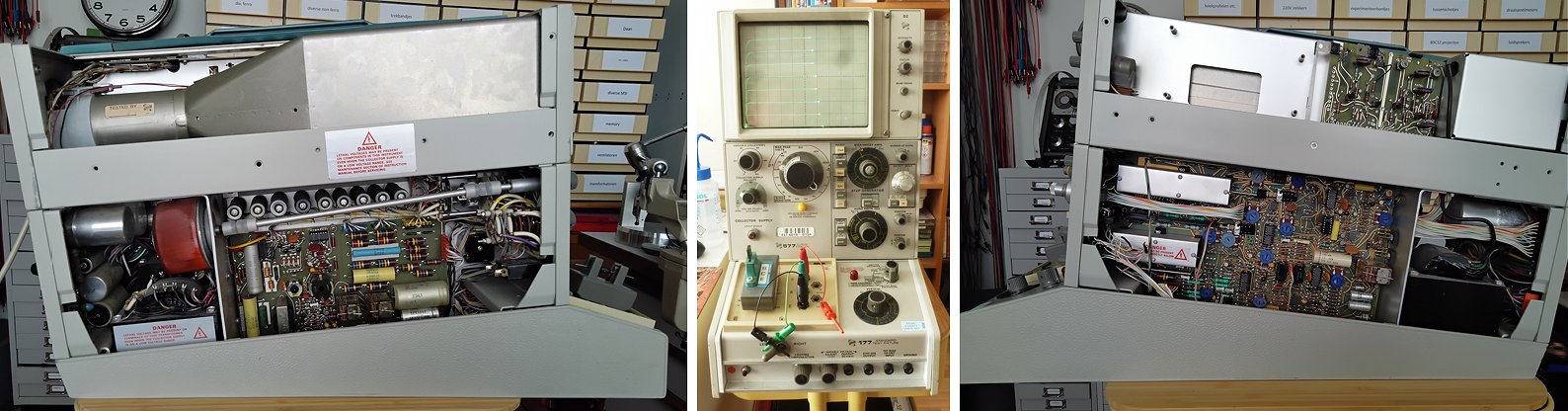

Something that has nothing to do with the uTracerNXT: some snapshots of my Tektronix 577 that my friend (and former colleague) Peter Blanken and I recently brought back to life. The first 20 years or so of my career at Philips Research, I worked extensively with a Tektronix curve tracer, be it the model 576. I have always missed one at home for quickly checking transistors and diodes. Luckily, sometime ago I was able to buy this more modern version 577 from our test equipment department for scrap-metal price. It needed some restauration but now it is fully functional again and has already shown its value during the repair of broken uTracers.

| to top of page | back to uTracer homepage |

Figure 7.1 Schematics (with some small changes) as they were used for Version 0 of the PCB for the uTracerNXT.

Figure 7.1 shows the schematics of the uTracerNXT as it was used for Version 0 of the PCB including some small modifications to include the selectable voltage ranges and with some renaming of components. Note that this is still a test version and that the schematics may still change during the development of the device.

Since the uTracerNXT is meant as a drop-in replacement of the uTracer3, the dimensions of the PCB and the locations of the drillholes were not changed. Also, the location of the power, heater and electrode terminals remained (more or less) the same. The only exception is the addition of a terminal block for the AC heater synchronization circuit.

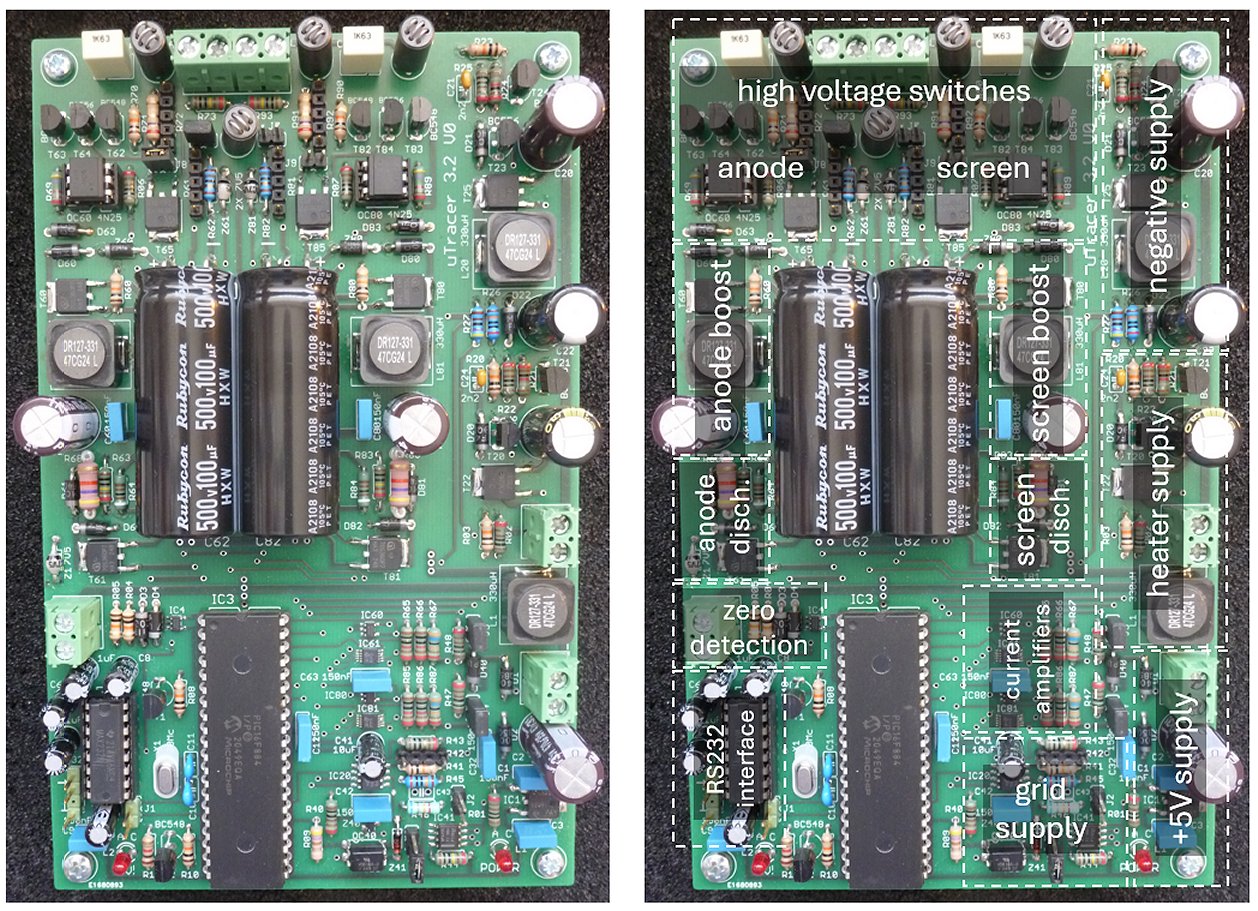

Figure 7.2 shows the PCB and the location of the different circuit parts. The layout of the PCB was a bit of a puzzle. First of all because there are quite a few components that all have to find their place. Next, some parts of the circuit carry a high-voltage, so that sufficient clearance to low voltage parts has to be taken into account. In some parts of the circuit, especially the boost converters, there are high (peak) currents flowing. These circuits parts have been provided with local 470 uF and 150 nF decoupling capacitors. Additionally, the areas enclosed by high current loops were kept as small as possible to minimize RFI radiation. Finally, there is the point of aesthetics; to satisfy my autistic urges I tried to make the layout as symmetrical as possible.

The high-voltage switches as well as the grid supply sections were provided with locations where additional resistors can be placed to modify current and grid bias ranges. In the build shown on Fig. 7.2, these locations are provided with modified pin-headers to facilitate quick and easy changing of resistors. The ranges can be selected by placing the appropriate jumpers. In the meantime, I also decided to add jumpers and resistor locations so that the anode and screen voltages ranges can be modified. These will be incorporated in a next version of the PCB.

Apart from a few text typos and some drill holes that were on the small side, the PCB worked first time without any layout issues. This is not a mean feat, since my version of Eagle only supports “polygon pushing” and no layout entry of layout versus schematic checking! As mentioned, this is just the first version of the PCB, and both the schematics and thus obviously also the PCB may be subject to changes.

Figure 7.2 Version 0 of the uTracerNXT.

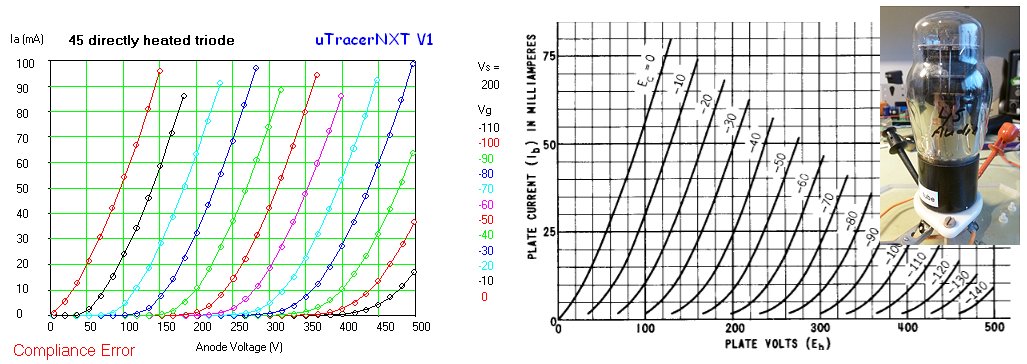

Figure 7.3 A nice illustration of the capabilities of the uTracerNXT, a set of characteristics of the among audiophiles well known 45 tube (left). On the right the same set of curves from the Tung-Sol datasheet. In this case the heater was powered by a transformer, making use of the new feature of the uTracerNXT to AC power directly heated tubes (see Section 6). For this measurement I set the compliance to 100 mA, to not unnecessarily push the current beyond that limit. Of course, the notice “Compliance Error” is not really an error, but a message that the uTracerNXT has skipped measuring the points above the set compliance value (100 mA). To speed up the measurement the range for the screen channel, which is of course not used, was set to maximum, avoiding unnecessary averages.

| to top of page | back to uTracer homepage |