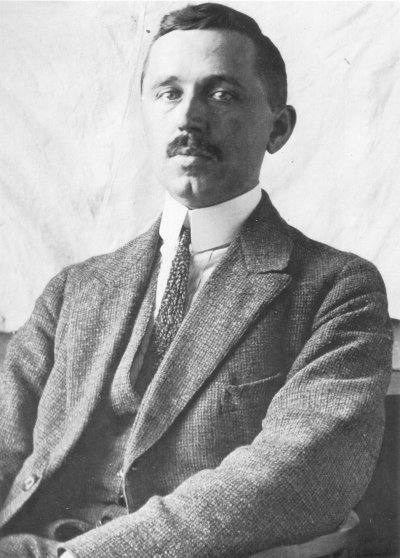

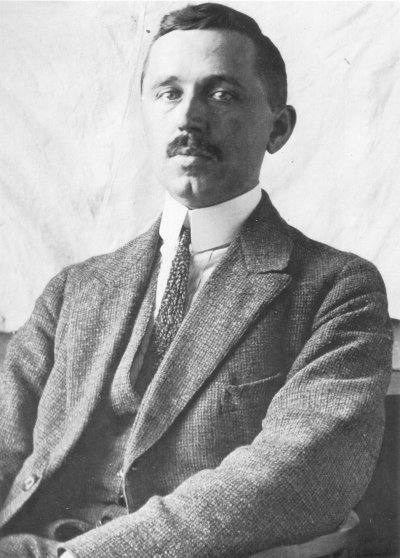

Being the second man to be employed in the Research Lab, Oosterhuis was almost automatically Holst’s second in command. Oosterhuis was born in 1886 in Zetten in the province of Gelderland. He studied at Groningen University where he obtained his doctorate in 1911 with a thesis entitled: “Over het Peltiereffect ed de Thermoketen van ijzer-kwikzilver,” (on the Peltier effect and the iron-mercury thermocouple). After that he worked as an assistant to Zeeman in Amsterdam and Onnes in Leiden. Zeeman won the Nobel Prize in 1902 and Onnes in 1913.

His Father, the son of a baker, received a grant to study theology. He discovered that he did not like preaching so he switched to mathematics and became a math’s master in a well-known boys’ boarding school. Oosterhuis inherited his father’s scientific ability and he was also influenced by being brought up in a very religious household. He had strong religious convictions and became President of the Union of Christian Schools. Oosterhuis married in 1916 and had three sons and two daughters.

Oosterhuis was as mentioned, the second scientist to on the Philips Research staff, joining on 16th of April 1914, just three and a half months after Holst’s own appointment. But seniority was not the sole reason for Oosterhuis’ position – he and Holst were a formidable pair and we must never underestimate Oosterhuis’ great contributions to the success of the laboratory; remember Holst describing him as my “geweten”, literally my conscience but not restricted to moral aspects. Older members of the Research Lab still remember him at meetings, a large cigar in hand, saying, ‘May I make a stupid remark?’ This was a warning, his remarks were never stupid and often exposed weaknesses in someone else’s argument. He was a man who was liked and respected by everyone in the Laboratory.

We get a glimpse of the man’s character by seeing that, despite a high salary, he came to work on a bicycle and never owned a car. Oosterhuis was always careful with his money, but was always prepared to spend it for good reasons. For example he built a beautiful summer residence at Leersum, some eight kilometers from Eindhoven where he spent his holidays with his family. Oosterhuis was not a great social man; he seldom read a book, worried little about his appearance and never went to parties. He was offered several university chairs, all of which he refused on the grounds that he did not like teaching.

As a leader Oosterhuis had a very pleasant way with his staff. He was always completely natural, friendly but matter-of-fact. Although he did not show it, he had great interest in all aspects of the laboratory and was always very well informed about all particulars of the work in progress. He never seemed to be in a hurry and often brought up subjects which had nothing to do with physics or with Philips, thus showing that he knew quite well that “all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.” The result was that he created a very relaxed atmosphere. When one met him in the corridor (this happened many times a day) he gave no sign of recognition, neither did he expect to be greeted, he thought that too frequent greetings would have made life complicated and unnatural.

When things moved slowly, he would sit down at one’s desk and talk things over. At a certain moment he might innocently say, ‘Let’s try and work this out together.’ The result was often that one suddenly saw a point which had hitherto escaped one’s attention, often indicating a new way of attacking the problem. When Oosterhuis had left the room one had the pleasant feeling that, with his help, one had taken a significant step. Later, however, one came to suspect that Oosterhuis had had the whole problem worked out in advance, the discussion had been a subtle way of communicating his findings without hurting one’s pride.

Oosterhuis took on the chief editorship of the Philips Technical Review in 1936. He continued this work until 1952, that is long after he had officially resigned as Deputy General Manager of the laboratory in 1946. As editor he got on with authors as well as he did with his colleagues, with great tact he made them accept changes without giving them the feeling that it was no longer their own article. Many authors of those days are still grateful for Oosterhuis’ constructive remarks about the style and presentation of papers.

After 1952 Oosterhuis only visited the Natlab on important occasions. He died in 1966 at the ripe old age of 79.